In early 2021 during the dark days of the pandemic, I started to write a novel narrated by a traumatized talking Raffles’ banded langur finding his way home to the jungles of Bukit Timah Nature Reserve at the end of the world.

In order to avoid coughing and coffins I walked and cycled a lot along the Rail Corridor. As I enjoyed the constructed green, several questions leapt into my thoughts and drove me into the arms of this novel.

The first question arose because of rejection. I had been chastened and humbled by an editor responding to a short story collection I’d sent him six months before. Not for him my bleak solipsism. He told me that my stories were well written and “somewhat” engaging, but they were also “relentlessly sombre” in pace, tone and sentiment. So, what on earth could I write next? Clearly, I needed to take a turn and write something fun. But we were in a pandemic. People were sick. The borders had closed. We were alone. The climate was in crisis. Obviously, I thought why not write an action-packed, dystopian novel that had hi-jinks and hope at its core?

Catching a wholesome respite from the confines of home, I strode up and down the Rail Corridor. Under the shade of towering Albizias, more questions occurred to me: what would living things say to us if they could speak? What would they write if they had the chance?

Nature can be cruel and beautiful at the same time. If animals spoke I was under no illusion that the conversation would be either coherent or kind. Birds would certainly be furious at the trees we’d chopped down. But could the creatures of the earth discuss their anger? Would ants want to explain what it’s like to be trodden on? Many living creatures may wish to kill us—surely, we’d given them reason enough—but query whether they’d be willing to articulate why? I expect if living creatures spoke, many would be indifferent. What’s the point, they’d say, turning away, locked in their own struggles to take care of their family, their homes and food sources destroyed by deforestation, the impact of the climate crisis, and declining biodiversity.

What would those living things who wished to speak say to us? “Thanks for everything? You guys and gals are the best thing since sliced bread?” I think not. Orcas are, after all, attacking boats.

Ideas alone do not make a novel. Novels are concerned with specific characters and the conflicts and tensions that they face. How could I dramatize the relationship between humans and animals and nature in a novel? I needed to create characters who could bear the burden of action and agency in uncertain times, and, despite their trauma, emerge optimistic and hopeful.

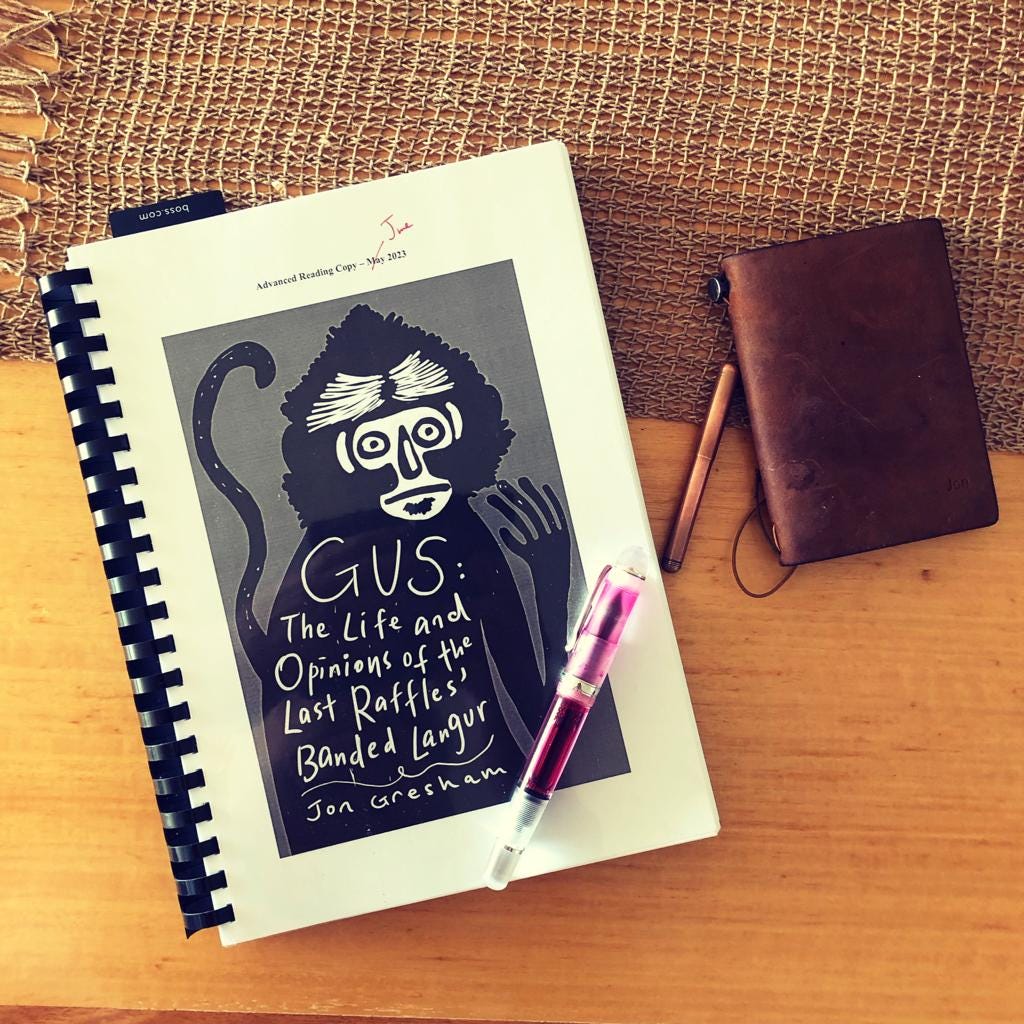

Who better than a Raffles’ banded Langur to carry the narrative? These primates are critically endangered primates found in Singapore and southern Malaysia. There are only about 70 in Singapore. They are shy and elusive, skilled at balancing, leaping and swinging from tree to tree, rarely coming down to the ground. They sport white bands on their underside and black fur on their body. In Singapore, they are the largest non-human primates still in existence. If only they could speak, what stories they would tell.

In the dreary, solitary, doom-filled days of the pandemic I came up with my key character, Gus: a weary, eloquent Raffles Banded Langur trying to get home to the depths of Nee Soon Swamp. In addition to Gus, I scribbled notes and drew pictures of my other key characters: an auditor who wished to be a clown, a Filipino nurse grieving after a family tragedy, a megalomaniac grey macaque, and a Pioneer generation, authoritarian police sergeant. All with numerous emotional and psychological issues. I imagined these characters under the greatest pressure at the end of the world.

As I read and walked along the Rail Corridor, I brainstormed ideas and drew character sketches. I arranged mood boards and mind maps for settings, atmosphere, and action. I named these fragments ‘The Blue Monkey Zombie Project’. I expanded characters by exploring their deepest yearnings and fears. I held my plot loosely and avoided all rational thought until I had some grasp of my characters unconscious motivations and delusions. I collected photographs of monkeys and free wrote their dreams.

I read Dr Andie Ang, the foremost primatologist in Singapore, and her book, Raffles' Banded Langur: The Elusive Monkey of Singapore And Malaysia, co-authored with Sabrina Jaffar. To explore my understanding of what it is to be an animal, I read JM Coetzee’s Elizabeth Costello and The Lives of Animals and some texts by Barbara Smuts, Thomas Nagel’s paper on What is it Like to Be a Bat?, William Olsen’s poem A Fallen Bat, Philip Larkin’s The Mower, Kij Johnson’s The Evolution of Trickster Stories Among the Dogs of North Park After the Change, and a wonderful Australian novel about communication between species sparked by a pandemic: Laura Jean McKay’s The Animals in That Country. I also read plenty of dystopian novels, such as Severance, Station Eleven, Day of the Triffids, Zone One, Children of Men and The Road. In order to preserve a smidgeon of positive sentiment I listened to The Kinks’ Apeman and The Monkees, and watched The Goodies on Top of the Pops doing The Funky Gibbon.

I purposefully avoided re-reading Karen Joy Fowler’s We Are All Completely Beside Ourselves or watching The Planet of the Apes movies. I wanted to view The Omega Man for dystopian inspiration but couldn’t find anywhere to download it legally. I promised myself that none of my characters would be Charlton Heston-esque, post-apocalyptic heroes relying on their individual skills and strength. Instead, I wanted my heroes to be vulnerable and committed to community and collective solutions. This is what contemporary eco-fiction needs. I reflected on Picasso and his study of a family of acrobatic clowns with a monkey. The 1988 painting Fear of Monkeys/Evolution by David Wojnarowicz was also an inspiration. This painting created at the height of the AIDs crisis touches on mortality and the natural world abused by man.

In writing the novel and finding narrative coherence I used the approach set out in Robert Olen Butler’s From Where You Dream: The Process of Writing Fiction. Only after I’d spent sufficient time tapping my own unconscious fears and hopes could I started to create scenes. I scratched these in pencil on index cards and began to order and rewrite the index cards seeking to find coherence amongst a tangle of characters arcs.

The tragedy of life seemed to inspire my drafts when I read about lonely Raffles’ banded langurs lost in concrete stormwater drains and hit by cars on the SLE searching for food.

Utilising my finance and accounting background, I summarised the scenes in complex spreadsheets detailing character motivations, key tensions (internal and external), tone and atmosphere, key images, important changes etc. Once I was happy with the basic story I re-ordered, scrapped, and outlined each scene and chapter again and again in rows on my spreadsheet. Then I transferred the outline and scene summaries to Scrivener and began to write each scene at the sentence level in detail. I rewrote and revised numerous drafts, always guided by, but never beholden to, my index cards and spreadsheet.

Eventually in August 2022, I submitted a draft manuscript to the Epigram Books Fiction Prize and was fortunate to be shortlisted and receive a publishing contract with Epigram Books. My debut novel, Gus: The Life and Opinions of the Last Raffles’ Banded Langur will be published in November 2023.

Gus is inspired by, and grieves for, the adverse impact of human development upon nature. The world faces existential crises — the climate crisis and declining biodiversity — all due to the impact of unfettered greed and human development. The novel shows how people and animals behave in Singapore as the world falls apart. In Singapore, we are taught to be functional, utilitarian and pragmatic and to see ourselves isolated from, rather than entangled with, nature. Nature is our tool, a means to human ends of profit and recreation. We forget how interconnected humans are with each other and with nature. The novel explores how our only future is together, finding new forms of kinship — beyond genetics, race, religion, corporations and countries — in care and shared experience. Whether or not the novel transcends the “relentlessly sombre” is for you the reader to judge.